A Senate Majority, If You Can Keep It

April 6, 2021

The Democrats’ twin victories in the Georgia Senate runoffs gave them a tenuous majority. With the upper chamber balanced at 50-50, Democrats’ ability to exert control depends on their ability to hold all of these seats in 2022 (and the vice presidency, which is guaranteed through 2024).

Can they do it? History might suggest no. The phenomenon of midterm loss is well-established for the House of Representatives: The president’s party has lost ground in every midterm election dating back to the end of Reconstruction save for three: 1934, 1998 and 2002. All three of those elections took place in unusual circumstances, where presidents had job approvals approaching or exceeding 70% (we presume this was the case in 1934).

In the Senate, however, the record is somewhat more mixed. The president’s party gained seats in 1886, 1898, 1906, 1914, 1934, 1962, 1970, and 2018. Notably, many of these Senate gains occurred in years that were otherwise rough for the president’s party; Democrats lost 61 House seats in 1914, while Republicans lost 40 in 2018.

The key insight is that not all Senate seats are up in every year, and where those races occur can have a significant impact on the outcome of the election. In 2010, Republicans won every Senate race in states that Barack Obama won by less than nine percentage points (with the exception of Joe Manchin’s run in West Virginia) and were a nomination hiccup in Colorado away from the races in states Obama won by less than 13 points. Had the Senate class of 2012 been up for reelection in 2010, Democratic losses could easily have run into the double digits.

That Senate class was up for reelection in 2018, which partially explains why four Democratic incumbents lost despite the negative environment for Republicans. This is all to say, Senate elections are affected by the national environment, but vagaries of the characteristics of the class that is up in a given year affects outcomes.

What should we expect, then, in 2022? Democrats have no room for error, given their razor-thin majority, but they have one thing going for them: This class hasn’t had a good Democratic year since 1998. Republicans ran well in 2004, and then pushed deeply into Democratic territory in the 2010 midterms. It was thought that Republicans would lose a substantial number of seats in 2016, but the party minimized losses by riding Trump’s coattails.

Put differently, Democrats simply don’t have much exposure this election. Democrats don’t have any incumbents up for reelection in states Trump carried, although two hail from states that narrowly went Joe Biden’s way (Georgia and Arizona). They have two other seats up in states that lean somewhat in the Democrats’ direction (Nevada and New Hampshire) and one in Colorado, which has elected Republicans narrowly in wave years but has since moved in the Democrats’ direction.

Republicans don’t suffer from a massive amount of exposure either, but they do hold seats in two Trump-then-Biden states: Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. Moreover, the incumbent in Wisconsin, Ron Johnson, has made some controversial statements recently, while the seat in Pennsylvania is open this time. The open seat in North Carolina will likewise be a tough hold, while those in Ohio, Iowa and Florida could come into play with retirements or with a good enough environment for Democrats.

To help sort this out, I’ve employed a model I first used back in 2014. The idea is that we’ve become so polarized that elections are primarily referenda on the party in power, and that senators’ fates are increasingly tied to the fate of the president. If a president of their own party is popular in their state, they will likely win. If he is unpopular, they will likely lose.

It also looks at whether the seat has an incumbent and whether one of the candidates is uniquely problematic (think: Sharron Angle). So, for example, Republicans may nominate candidates who would have a difficult time winning under any circumstance in Georgia or Arizona, depending on how things shake out. As a final note, it only takes into account modestly competitive races, on the theory that “safe” races are effectively drawn from a different distribution (i.e., they are fundamentally different than races that are rated competitive).

The model isn’t intended to get every race correct: It systematically under-predicts Joe Manchin’s chances, for example. The idea is that there will be errors in individual races, but they will tend to cancel out. In other words, it doesn’t shoot for accuracy in particular races so much as it shoots for unbiased-ness.

It has performed well over the years. In 2014, it suggested that if Barack Obama’s job approval were 44% on Election Day then Democrats would lose around nine Senate seats. This is what happened. In 2016, it suggested Democrats would gain three seats if Obama’s job approval were 52% on Election Day; they gained two. In 2018, it said that Republicans would gain a pair of Senate seats if Donald Trump’s job approval hit 45%; that is what happened. In 2020, a 47% presidential job approval translated to a wash; as of Election Day they had lost a seat. The model would also suggest that Republicans’ eventual loss of the Georgia Senate seats in January was mostly a function of Trump’s declining job approval in the interim.

So what does the model see for 2022? Figure 1 shows the outcomes for 10,000 simulated elections across the five seats held by Democrats and seven held by Republicans, based on Biden’s current job approval rating of 52%. It likes the Democrats’ chances of picking up a seat. Perhaps most importantly, they also would have strong likelihood of defending their seats. It would see Pennsylvania and North Carolina as solid pickup opportunities. It might like Ron Johnson’s chances in Wisconsin too much – he arguably should be classified as a “problematic” candidate at this point – but it also might be too bullish on Democrats in North Carolina, given their recent track record there. Likewise, if Christopher Sununu runs for the Senate in New Hampshire, Republican chances would improve there.

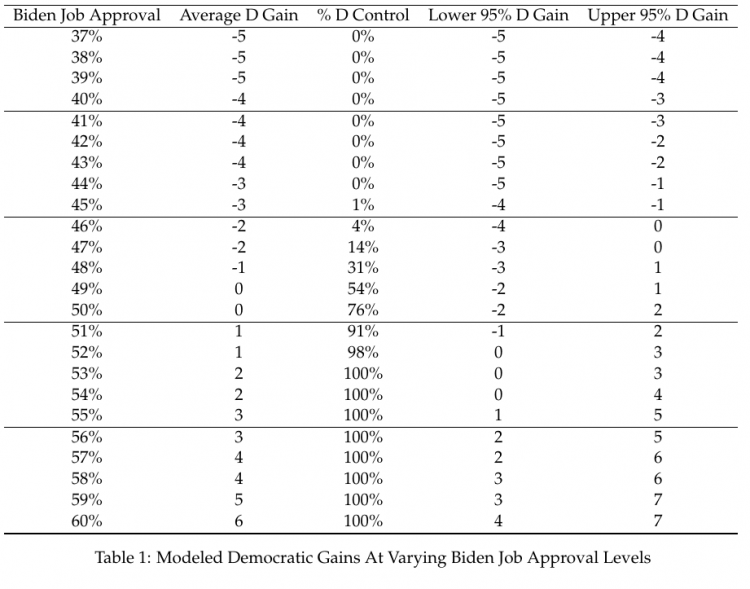

Of course, President Biden’s job approval is probably not going to be 52% on Election Day 2022. It could be higher, or it could be lower. To account for this, I ran 10,000 simulations with his job approval at every level between 37% and 60%, which seem like credible outer bounds for where his rating could wind up.

As you can see, Biden isn’t that far off a job approval where he could see significant gains in the Senate — enough to almost certainly jettison the filibuster and enact a wide-ranging agenda. Just four points higher, at 56%, Democrats would be expected to gain between two and five seats. But he also isn’t that far off a job approval rating where things would go very poorly: If he enters the midterms at 45% — roughly where presidents have been for the last four midterm elections — Democrats would lose between one and four seats, possibly setting Republicans up for a massive Senate majority after the 2024 elections.

The break-even point appears to be around 49%. At that number, we would expect the Senate outcome to be very close, with Republicans roughly as likely to take the Senate as Democrats are to keep it.

Of course, like all models, no one should take this too literally, and (more importantly) the error margins are real. As the great statistician George Box famously put it, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The utility here is probably in generating reasonable bounds on our expectations. Democrats probably are favored to retain the Senate for now, but their outcomes are tied to their president’s performance, and they don’t have much room for error.

Leave a Reply